A British machine gun team at the front line during World War One. A game of football would have been the last thing on their minds-and yet…. (Shutterstock)

In 1914 Great Britain declared war on expansionist Germany.

Thousands rallied to the cause, enthused, undoubtedly, by feelings of patriotism and a compelling urge to ‘do their duty’. There was also the popular belief, held by many, that the war would be short, swift, and, as far as Britain and her allies were concerned, ultimately victorious.

With a gilt edged opportunity for a nations youth to experience both the thrill of action as well as the satisfaction of conquest, who could blame any of the thousands and thousands of men who signed up to fight?

Many of them ended up fighting alongside their friends in the hastily formed Pals battalions, specially constituted fighting units that comprised of men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives with the promise they would serve alongside their friends, neighbours and work colleagues.

Our very own Royal Norfolk Regiment, formed in 1881, would certainly have included lots of ‘pals’ within its ranks. It entered the First World War with two regular, one reserve and three territorial force battalions, eventually expanding to nineteen battalions in total. Posters displayed in Norwich asking for more volunteers asked for men to “Come and join our happy throng” as the recruitment drive picked up the pace. Clerical staff from the Great Eastern Railway served together with the 34th Division Signal Company, Royal Engineers (Norfolk Battalion)-an example of a ‘Pals’ battalion and one of many.

The old Britannia barracks in Norwich, a familiar sight to the men of the Royal Norfolk Regiment (Evelyn Simak/geograph)

It did not take long for the grim reality of war to overtake the romance.

The first battle of the Marne started on September 5th 1914-a battle that would ultimately result in tens of thousands of casualties and, in its stalemate, putting a swift and bloody end to the notion that it would ‘all be over by Christmas.’

Yet, despite the dawning realisation that the country was involved in a conflict that would be long, costly, and deadly, much of life, ‘back home’ went on as normal.

On the same day as the Battle of the Marne started for example, so did the 1914/15 English football season.

Arsenal lost to Wolves, Tottenham drew with Chelsea.

And Norwich City, then playing at The Nest and a member club of the Southern League, travelled to Cardiff, losing 1-0 to Cardiff City in front of 5,000 spectators.

The same fixture the previous season had seen a crowd of 15,000 spectators.

Why the sudden and drastic drop in spectator numbers in a game that was becoming increasingly popular with large crowds at games become more and more the norm?

Because all the young men that used to go and watch games had signed up to fight.

As far as those young men who played it were concerned however, the Football Association (FA) refused to consent to their players of the time leaving their clubs and the game in order to sign up.

In competitive cricket and rugby, organised play had been suspended in order that they might do so-indeed, at Leicester Rugby Clubs ground at Welford Road, the RFU requested its members to turn up there and sign up as a playing unit-we can assume the players were drafted into one of the ‘pals’ units, rugby and cricket players training and fighting together.

The FA felt that to cease football in a similar manner would be a blow to the morale of the nation and that organised football must continue. The President, Lord Kinnaird, refused to permit it-the FA and the clubs were powerful, players were warned that if they left to join up, they would be in breach of contract.

The players union (PFA) was new and had only 300 members-it was powerless to act on behalf of its players. So both they and the game struggled to continue, regardless of the FA’s conviction that regular football would act as a morale booster to the nation.

As a consequence, both players and administrators were asked to take salary cuts. Norwich City players agreed to a 25% reduction in their salaries whilst the clubs Manager, James Stansfield, volunteered a 40% reduction in his.

With the nation now resolute in doing whatever needed to be done in order to emerge from the worsening conflict as victors, the FA soon realised that their stance on refusing players permission to join up was a hopeless one and footballers steadily drifted away to join up regardless of what the FA had decreed.

Norwich’s Captain at the time, Jock MacKenzie joined up, becoming a Lance Corporal in the Royal Garrison Artillery. He was awarded three stripes and two medals, taking part in the allied engagements at Gaza and the subsequent advance to Jerusalem.

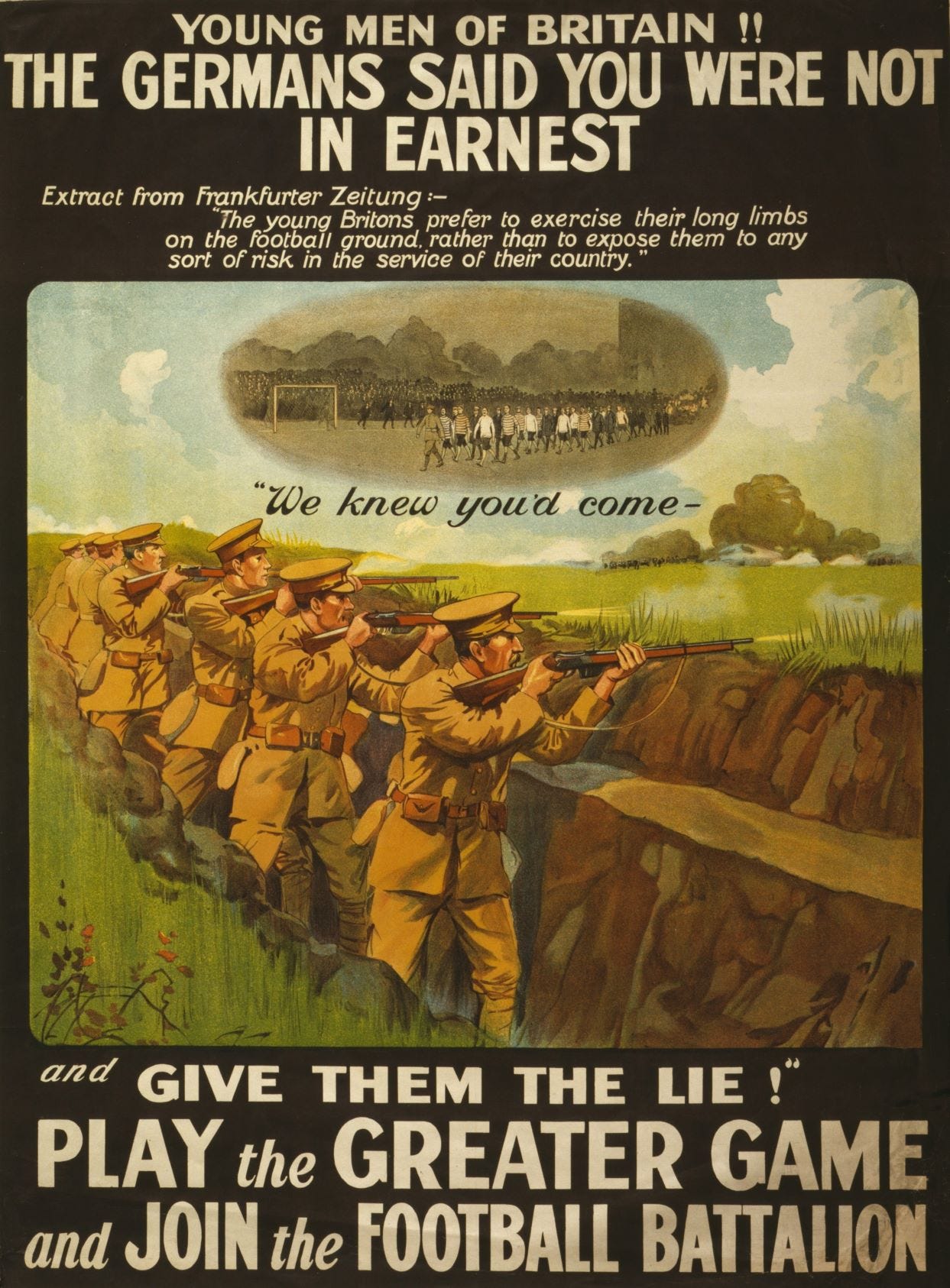

A Footballers Battalion was formed in order to attract the men who made their living from playing the game. Most of them didn’t need an incentive… (Shutterstock)

Then there was Philip F Fullard.

He was born in Wimbledon in 1897 before being educated at the King Edward VI School in Norwich where he captained the school football and hockey teams. He eventually signed for the Canaries and was a regular for the clubs reserves-but never played a first team game.

Fullard was typical of the ‘well off gentleman’ of the time-respectable background, a good education and both time and money to spare in order to partake of a little competitive sport now and again, including his time with Norwich City. But, equally, as a ‘gentleman’, he also had his own ideas as regards his duty to King and Country and signed up, originally commissioned as an officer into the Royal Irish Fusiliers.

But, in April 1914, he opted out of his regiment to join the Royal Flying Corps having learnt to fly- at, needless to say, his own expense what was still an extremely dangerous pursuit-and, as for airborne warfare, it was almost totally unknown. Parachutes were not considered “sporting” at this time and pilots were not issued them initially as it was believed having a parachute would make them less brave, more likely to save themselves than press home the advantage.

Despite this, Fullard went onto become one of the most successful fighter pilots of the Royal Flying Corps with 40 victories. But, two days after his 40th combat victory he suffered his first injury of the war, a compound fracture of the leg. He did this playing football in a match between his squadron and an infantry battalion-you suspect the players in the infantry team were only too glad to make their acquaintances with the ‘fly boys’. The injury was a particularly serious one and Fullard did not return to duty until the end of World War One.

How ironic that he was spared the horrors of the battlefields because of an injury sustained on a rather more prosaic field of green.

But what of Jock MacKenzie, the pre-war Captain of Norwich City?

He’d spent his war years in Africa, serving in the Royal Garrison Artillery, returning to the game soon after the end of the conflict in 1918. He made no further appearances for Norwich in a career that ultimately saw spells at Hearts, Millwall, Newcastle United and Millwall, dying at the ludicrously young age of 55 in 1940, having fought through one war, but not being fortunate enough to live to see the end of another.