A last line of defence against Hitler’s invading forces at North Lopham (Keith Evans/geograph)

Talk of a new Cold War a few years ago between the post-WW2 definition of ‘East’ and ‘West’ has now been superseded by the reality of a new one as a result of Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s expansionist policies into nations that once formed part of the old Soviet Union as the greedy eyes of the great Russian bear eye up the likes of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and even Finland; targets all once his relentless quest to pacify and conquer Ukraine is done.

The world is, once again, teetering on the precipice of a far wider and potentially more disastrous conflict than any that have been seen before, the definitive ‘war to end all wars’ if ever there was going to be one.

Norfolk will, of course, be one of many frontlines in the event of a new battle between Putin and his allies and a rattled and ill-prepared west, not least when (rather than if) the proposed purchase of nuclear capable aircraft for the RAF goes ahead, planes that will be based at airfields across the region.

But then Norfolk has always been something of a military hotspot.

Coastal towns such as Great Yarmouth and King’s Lynn were the first ever to be bombed from the air during World War One when the German Navy Zeppelins L3 and L4 bombed the towns in January 1915, attacks that killed four civilians whilst injuring sixteen others.

Wars had always been fought in foreign fields as far as the people of Great Britain were concerned, snippets of far away news to be served with breakfast on a daily basis.

This was a war that had crossed the water and knocked, firmly and with no fear, at John Bull’s front door.

That reality was rendered even more stark when the commencement of World War Two.

As the sequel to the Great War loomed, Norfolk’s coastline was transformed into a frontline of its own.

Villages and seaside towns that once thrived on fishing and holidaymakers braced for invasion. The threat of German forces landing on the counties wide and conveniently flat beaches precipitated a rapid mobilisation of civil defences.

Barbed wire snaked across the sands, concrete pillboxes were poured and set into dunes and field margins, and anti-tank obstacles littered country lanes and coastal tracks whilst church towers and farm buildings became observation posts.

The Home Guard, dismissed as part-time soldiers, took their duties with quiet determination. Drawn from farmers, shopkeepers, retired officers and those too young or old for regular service, they drilled in village greens and on field and marshes, armed at first with little more than armbands and broomsticks. Gradually, rifles, uniforms, and training followed.

Their mission was clear: defend the coastline, delay any enemy force, and buy time for the Army to respond.

The statue of Captain Mainwaring from Dad’s Army in Thetford. Putting the laughs aside, the Home Guard were, as one, exceptionally brave and selfless men (Peter Trimming/geograph)

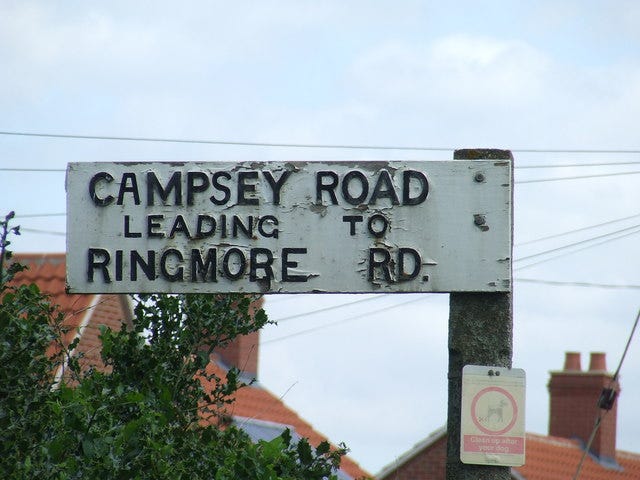

Along the Broads and waterways, patrols watched for German paratroopers. Road signs were removed to confuse invaders. At night, blackout curtains turned towns into darkened silhouettes, and air raid wardens paced the streets, ensuring not even a glimmer of light betrayed a home.

Road signs like this one (near Southery) would have been taken down in 1939 (Keith Evans/geograph)

Norfolk now stood ready—not just as a place of resistance, but as a symbol of how ordinary people quietly prepared to meet extraordinary times.

So how did the county prepare itself for World War Three?

One site in Norfolk that was strategically important at the time for reasons which it is perhaps best not to think about too much was the high security (you would hope) storage facility for nuclear weapons that was set aside at RAF Barnham, just two miles to the south of Thetford.

Nuclear weapons were held at the station throughout the fifties and sixties, a fact that, if it was relatively unknown at the time, would certainly have become one more apparent to local residents if the UK had ever been close to nuclear war, so busy would the station have been with large vehicles arriving, probably in the early hours of the morning, to start shifting part of its deadly arsenal to wherever it might have been needed.

One of the stations major purposes was, along with its sister site at RAF Faldingworth, to serve the soon to be formed Vulcan V-Bomber Squadrons and their lethal payloads.

Storage buildings at RAF Barnham. They look innocuous enough but each of them would have been ‘home’ to a nuclear warhead. (Evelyn Simak/geograph)

These once familiar delta-winged aircraft were unique in that they were able to head far enough east to be able to drop its bombs onto enemy territory in what would almost certainly been a one-way trip for its crew, simply because there would more than likely have been no RAF bases left for them to return to upon the completion of their duties.

Prior to its use as a nuclear depository, RAF Barnham had another deadly use as it had been previously used during the Second World War as a chemical weapon storage facility and filling station as well as being used as a bomb dump for ‘conventional’ ordinance.

During the years of the Cold War, RAF Barnham would certainly have been a site known to enemy intelligence and, if it had not been prioritised as a target for a first strike would almost certainly have been targeted in any second wave of enemy nuclear missiles, the consequence of that meaning that much of East Anglia as we know it would have been permanently removed from the map.

And it wasn’t as if RAF Barnham would have been the only possible enemy target of Warsaw Pact forces in the county.

How do you think the residents of that part of Norfolk would have felt or reacted had they noticed the heightened activity around the base, the increased security, roadblocks and numbers of military personnel that would have preceded the sight and sound of those three Thor missiles launching and heading towards the former USSR?

Their launch would soon have been recorded by enemy forces whose retaliation would have been swift…

…and deadly.

How would you have spent the last few minutes of your life on a chilly October afternoon in what was, now for a very short time indeed, one of the quieter and more unspoilt parts of rural Norfolk?

The stark reality of the time was that Norfolk and Suffolk had little choice with regard to the sacrificial roles both the respective counties and their population would have been left to make at that time and throughout the Cold War.

East Anglia was on the front line through nothing more than its geographical position and the number of sites that had already been established there for exactly the same reasons they had during the Second World War. The region subsequently contained nuclear weapon stores like the one at RAF Barnham as well as missile launch sites, military airbases, radar and intelligence stations and nuclear research facilities.

Another important base was the former RAF Sculthorpe near Fakenham which was extensively refurbished for the USAF after the Second World War during the Berlin Crisis in 1949.

Three years later it became the home base for the USAF’s 47th Bombardment Wing and the 49th Air Division. The rapid increase in the Soviet Union’s conventional forces in eastern Europe had meant that US-led NATO felt it had no choice but to do the same with their own forces and their overall presence in western Europe as a consequence.

NATO did this by introducing the US bomber aircraft the B-45 Tornado to Sculthorpe, planes that were capable of carrying and dropping up to five nuclear bombs each. In addition to this, the Pentagon decided it would also redeploy the 47th Bomb Wing to Sculthorpe from their previous base in Virginia, the first redeployment of US military personnel anywhere since the Second World War.

RAF Sculthorpe photographed from the air last year-runways all still open and very much operational (Simon Tomson/geograph)

RAF Sculthorpe is now ‘operationally closed’ and the site of, according to plans now widely available, a future museum.

‘Closed’? 😁

Don’t believe it.

The main runway, once mooted as a potential emergency landing site for the space shuttle is still operational whilst the site itself could be restored to full offensive capability in a few weeks.

You may have seen these odd looking aircraft flying in and out of RAF Sculthorpe in recent months. The Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey is an American military transport and cargo aircraft. (Wikiwand)

The stakes and risks then, just as they are now, were enormous, the chance of conflict one that grew, day by day and hour by hour. Yet few who travelled the narrow and lonely roads around the base at Sculthorpe would ever have guessed not only how close they were to coming to oblivion but also just how close they were to a significant part of the war machinery that would have contributed to it.

Because, even if you lived and worked in the region throughout the entire Cold War, RAF’s Barnham and the USAF bases at Sculthorpe and the surrounding areas would have become so much a part of your day-to-day life and scenery you might well have almost forgotten that they were there, despite these facilities and their strategically vital personnel being all around you.

However, had the very worse happened and the three minute warning been sounded, many of those who, day by day, might have been in the shop or pub with you would have long faded into the background, already preparing for multiple launches and the inevitable retaliatory strikes, safe(ish) in secure underground facilities.

Another (there are many) reason that Norfolk is very much in Russia’s sights (Adrian S Pye/geograph)

Whilst you, I, and everyone else would have been expected to make do with a door propped up against an interior wall and held in place by sandbags.

Exactly the same advice we will be offered if the conflict that everyone dreads and no-one wants yet all in power, civil and military, are now expecting and planning for by 2030, breaks out sooner than that.

It might well have been known both then and now as the Cold War. Yet if it ever reaches the conclusion that nobody wants, Norfolk would, will, very swiftly and irrevocably be converted to obsidian, becoming, in the process, one of the hottest and bleakest spots on the entire planet, a county that was, and remains as far as potential global conflict is concerned, anything but in the middle of nowhere.

Unfortunately for all of us.

![[object Object] [object Object]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!b4ZB!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F62e299cd-3a66-4706-bbfe-62100166bd2f_1286x918.jpeg)

Scary.