Norfolk's Space Race

Who'd sit at school dreaming about driving a steam train when you could live in Norwich and be an Astronaut...

It used to be the dream of every young schoolboy-and not a few girls come to that-to be an steam engine driver.

It was easy to understand why. The locomotives of the time were everything excited youngsters could identify with.

They looked fabulous. They had evocative names like the Atlantic Cross Express, the Bon Accord, Mallard, Broadsman (which took passengers from London Liverpool Street to Sheringham and Cromer), Comet and the Torbay Express.

Steam action on the North Norfolk Railway near Weybourne. Every young schoolboys dream…until, that is…? (Derek Harper/geograph)

Plus they were fast, dirty and very noisy.

They even talked to you as they thundered past. “Look at me-look at me-look at me-look at me-look at me…….”

Perfection.

Perfection, that is, until the space race kicked in which would have been the early-mid 1960’s and beyond.

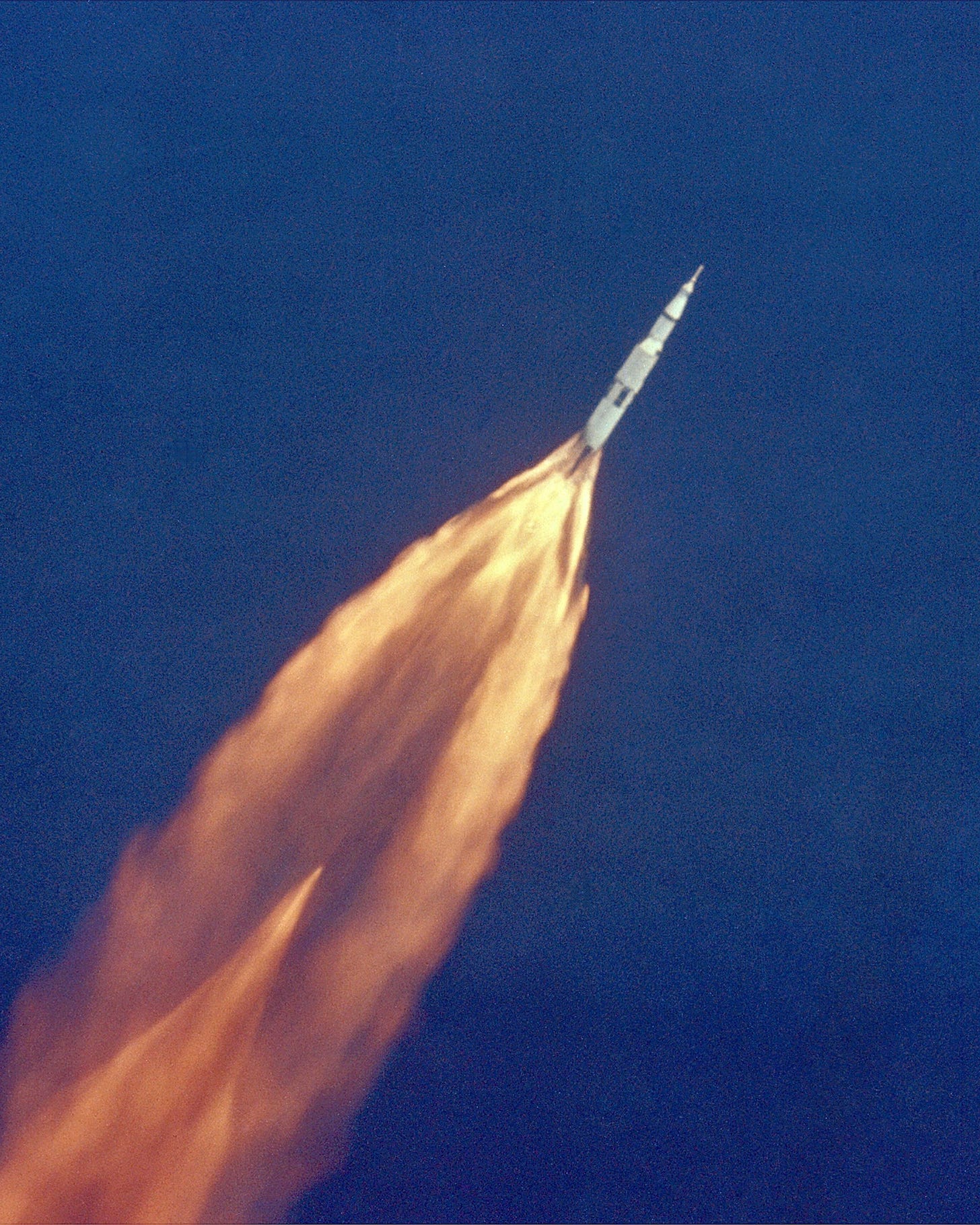

Those craft had even more evocative names. Thor, Atlas and Titan. Plus the iconic Saturn V, the monstrous launch vehicle for the Apollo moon missions.

…the Saturn V launch vehicle that took the crew of Apollo 11 to the moon. A living, breathing, snorting and snarling behemoth. Which might have been seen in the skies over Brancaster (Shutterstock)

Plus they were faster, dirtier and much, much noisier.

Thus, in a heartbeat, small children all over the nation wanted to be astronauts instead.

Yet such dreams were more than a world away for us in Norfolk. They were more remote than the distant reaches of space that the craft sought to explore, distant and impossible realms. Whereas you could, at least, still see a steam train pull into Hunstanton every day.

Not so glamour ridden, sure. But more realistic.

Yet even if Norfolk couldn’t come to the space race, the space race very nearly came to Norfolk.

Not surprisingly, bearing in mind the political and strategic potential that a space programme might bring to the nation, the British Government was very keen on possessing a space port to call its own, our very own version of, as it was then known, Cape Canaveral. We had, after all, a thriving space rocket programme which included three separate launch vehicles-Blue Streak, Black Knight and Black Arrow.

The search for a British launch site to match Cape Canaveral eventually produced a short list of three possibilities. One, situated on the Outer Hebrides was considered and then swiftly rejected because of concerns over poor accessibility and weather conditions that were, at best, unpredictable. Florida it most certainly wasn’t.

Similarly considered and rejected was Woomera in Australia. A good site yes with a more reliable year round climate. But it was in Australia, not only distant but, in an ever changing political landscape, a location that might, one day, have not been the UK’s to make use of.

This left those charged with making the decision one possible site remaining. Which was in North Norfolk.

Or, to be more precise, on the coast at Brancaster.

It all seems fantastic now, fantasy even, a story of epic, even April Fool proportions. But it is a true one.

Brancaster really was seriously considered as the site for a British spaceport.

Brancaster beach-the one time proposed home of the British space programme (Pam Frey/geograph)

It had a lot going for it. And I don’t mean the long coastal walks, the beaches, the pubs and clean, fresh seaside air.

It was in the UK. And it was convenient. Far enough away from London to not a potentially hazardous neighbour yet near enough to be accessible. Furthermore, Brancaster was also relatively close to Hatfield and Stevenage, both important centres at the time for the British space industry but, at the same time, it was remote enough and offered enough land and capacity for a large site that would need to include not only the site for the launches themselves but room for the numerous support buildings and storage facilities that would also be required.

Furthermore, launches from the Norfolk coast were, logistically, almost perfect as its proximity meant a clear run out and over the North Sea towards the polar icecaps.

Quite what would have happened to the existing villages of Brancaster and Brancaster Staithe had the plans been given the green light is open to question. But there is a very real possibility that, just like Imber and Tyneham, two villages that were compulsorily evacuated by the MOD during the World War Two for the good of the war effort, Brancaster might, for reasons of science and politics, have suffered a similar fate.

The remains of Tyneham village in Dorset. Requisitioned and abandoned. Brancaster might have suffered the same fate (Michael Dibb/geograph)

As it is, the only low flying and occasionally erratic objects to be seen on its coast these days are the golf balls that members of the Royal West Norfolk Golf Club regularly attempt to send into orbit.

Luckily for Brancaster, it was an equally stellar discovery that had its origins in the icy waters off the Scottish coast that saved it from suffering a similar fate to Imber and Tyneham.

The discovery of North Sea oil meant that oil rigs were rapidly being constructed and positioned in the North Sea meaning that, ultimately, that clear run of sky and sea between the coast, the North Pole and the enormity of space above and beyond all of that was, suddenly, not so clear after all.

Rockets launched from the site would almost certainly have had, much like the Saturn V, to shed at least two stages during their ascent from the coast to the chilly cosmos. And, with those oil rigs gradually spreading all over the North Sea, the possibility of one of these rocket parts striking an oil rig or one of the many support vessels in the vicinity was declared too great a risk to take.

It was a small one of course. Yet the implications and effects of such a catastrophe happening were, as far as the UK Government was concerned, too considerable a risk to take.

Though you also suspect that, given the costs of building a spaceport from scratch would, even then, have stretched into the tens of millions, possibly hundreds, perhaps it also gave them a convenient way out of what would have been a considerable financial, political and, significantly, controversial plan.

It’s fate was also partially sealed by advances in technology.

It would have been folly to imagine that any spaceport at Brancaster would have been devoted to scientific advancement and for, “...peace and goodwill for all mankind” as Neil Armstrong famously said when he stepped onto the surface of the moon.

A noble concept. But not what would have been the case in reality.

It is quite likely that the launch site would have comprised of a runway of extraordinary length, one that would have been able to support not a space rocket that was launched in the conventional sense but a space plane, much like the Space Shuttle-but one that did not require a separate launch vehicle to get it into space in the first place.

British Aerospace and Rolls Royce had long dreamt of developing a reusable space plane that they called HOTOL-short for Horizontal Take Off and Landing. The idea is still being considered and practiced today, not least by Sir Richard Branson and his Virgin Galactic project.

But back in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, it was rocketry’s holy grail.

The saving grace for Brancaster came, again, through the development and introduction of new technology. Advances in electronic surveillance techniques meant that it was not, after all, practical or even necessary to need a space going vehicle that could take off and observe the USSR from space before returning back to earth, complete with its espionage related cargo.

Cameras, for at least that purpose, were becoming obsolete. East Anglia did still play its part in the both the rocket testing and spying game. Only the site that took on the responsibility to do so was now being built and used in Foulness, off the Essex coast, a site that is, to this day, still owned by the MOD and where access remains restricted.

Foulness island in Essex. Don’t even think about landing your boat there (Robin Webster/geograph)

However ludicrous the concept might seem today, given the fate that befell Foulness, it seems that Brancaster suffered a lucky escape and that we are more fortunate than we think to be able to enjoy its (relatively) undisturbed and magnificent beach as it was intended, today and for always.

….at least that’s what they would like us to think anyway…

![Tyneham village [2] by Michael Dibb Tyneham village [2] by Michael Dibb](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KepA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9ba50d17-cad4-42dd-af6a-188a3e212bfb_640x480.jpeg)